Last Gasps

Paranormal

The South’s science-based team!

Our trained investigators are here to believe you. Most importantly, we are here to solve the problem...no matter what it takes. Our services are always FREE.

© 2023 Last Gasps paranormal. Links | Terms and Conditions

Marietta City Cemetery

Marietta, GA

Considered to be one of the most haunted places in Georgia, the Last GASPS has actually had the pleasure to spend a great deal of time in this wonderful cemetery. The cemetery is actually two cemeteries side by side. The Marietta City Cemetery is the older of the two and then the Confederate Cemetery houses our war dead.

Written by Kyle T. Cobb, Jr.

Nos tibi credere.

Haunted Places

Marietta Old City Cemetery

History

The village that became Marietta traces its origins to an illegal settlement of a small cluster of homes near the Cherokee town of Kennesaw in 1824. In 1832, the state of Georgia authorized settlement from the lands newly acquired from the Cherokee and the town of Marietta was recognized on 19 December 1834 using a plat laid out by James Anderson. While the new county was named after Thomas Willis Cobb (a US representative, Senator and Supreme Court Judge), Marietta was named after Cobb's wife Mary.

Even before Marietta was established the cemetery had its first burial. The unfortunate first grave in the cemetery was the 8-year old son of William and Mary Harris. The first grave read:

Here lies the remains of

Wm. Gapers G (for Gabriel) Harris

Who was born Apr. 6, 1823

Died Dec. 11, 1831

As you pass by so once did I

It is probable that the actual burial took place sometime before 1833 but the exact date is uncertain.

The plot of land that became the cemetery was originally awarded to Mrs. Francis Berry in the 1832 Cherokee Land Lottery, but it seems Berry never took possession of the land. Harris had won another tract of land but appears to have been a land speculator and purchased a number of tracts from lottery winners. Harris had been born in North Carolina in 1780 and by the time of the 1832 was a wealthy planter and had served in the Georgia House of Representatives in 1814.

While the young Harris was the first grave, he was not alone as not too far from his grave a small church building was erected in 1833. The building served the Methodists, the Baptists and the Presbyterians but by 1835 it was abandoned for their more permanent structures near the town square.

Some years later, the land became a proper cemetery and several other burials occurred. The next earliest confirmed burial was that of Victoria E. Randall (July 7, 1838). Robert R. Randall followed around 27 April 1839. Presbyterian Hannah Simpson was buried there around 27 July 1839. There are likely a good number of other burials from the 1830s that have been lost to time.

One unique feature of the Marietta City Cemetery is the inclusion of a Slave burial lot. At the time of its creation, no other major cemetery in Georgia allowed the burial of slaves or free people of African descent in the same graveyard as whites. The existence of the slave portion of the cemetery would have been lost to history it Robert E. Lawhorn, the city clerk of Marietta had not assembled a complete record of the cemetery.

There is some evidence that a second church, the first Methodist church had a log cabin in the cemetery near the slave section around 1835. Both the cabin and the records to support this contention are long gone. There was also a Methodist parsonage located at the northwest corner of the cemetery that borders what is now Powder Springs road. Eventually, the parsonage fell into disuse and was eventually owned by former slave Moses Bacon in 1873. The Timmons plot still retains a marble corner post placed by Moses Bacon with the inscribed initials MB.

Mary Phagan

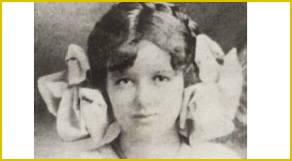

The most celebrated burial in the City Cemetery is 13 year old Mary Phagan. In 1913, the murder of Mary was the South's most spectacular murder case and won the hearts and outrage of Georgians.

Mary Phagan was born into a family of tenant farmers on 1 June 1 1899 in Florence, Alabama, four months after her father William Joshua Phagan died of measles. Phagan's mother moved her family to East Point, Georgia, to opened a boarding house and the children were sent to the mills for work. By age 10, Mary was working in a textile mill and in 1911, she went to work in a paper manufacturing plant. In spring 1912, her mother remarried and the family moved to Atlanta. Mary took a job inserting erasers into wooden pencils at the National Pencil Company for $4.05 a week (working 50 hours!).

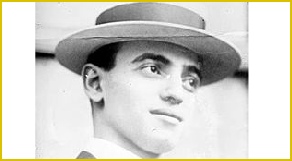

Mary worked on the second floor of the factory in a section called the tipping department, down the hall from Leo Frank's office.

On 21 April 1913, Mary had been laid off because of a shortage of brass sheet metal. Around noon on 26 April, Confederate Memorial Day, a statewide holiday honoring Confederate veterans, she went to the factory to collect her pay of $1.20.

At about 3:17 a.m. on April 27, the factory's night watchman, Newt Lee claimed to find the body in the factory basement. Mary Phagan's body was found dumped in the rear of the basement near an incinerator. Her dress was hiked up around her waist and a strip from her petticoat was torn off and wrapped around her neck. Her face was blackened and scratched. Her head was bruised and battered. A seven-foot strip of quarter-inch wrapping cord tied into a loop was around her neck buried a quarter inch deep. Initially, there was an appearance of rape. Based on the ashes and dirt from the floor that were stuck to her skin, it appeared that she and her assailant had struggled in the basement.

A service ramp at the rear of the basement led to a sliding door that opened into the alley; the police found it had been tampered with so it could be opened without unlocking it. Later examination found bloody fingerprints on the door, as well as a metal pipe that had been used as a crowbar. Some evidence at the crime scene was improperly handled by the police investigators. The boards from the door with the bloody prints were removed and subsequently lost before any analysis could be done. Bloody fingerprints were found on the victim's jacket, but there is no indication that they were ever analyzed. A trail in the dirt along which police believed Phagan had been dragged was trampled and no footprints were ever identified.

Two notes were found in a pile of rubbish by Phagan's head, and became known as the "murder notes". One said: "he said he wood love me land down play like the night witch did it but that long tall black negro did boy his slef." The other said, "mam that negro hire down here did this i went to make water and he push me down that hole a long tall negro black that hoo it wase long sleam tall negro i write while play with me."

The effect of the discovery was to cast suspicion on Newt Lee. During the trial, "night witch" was interpreted to mean "night watch[man]"; when the notes were read, night watchman Newt Lee said, "Boss, it looks like they are trying to lay it on me" (or words to that effect). An undisturbed fresh mound of human excrement was found at the bottom of the elevator shaft, though the significance was not recognized until after the trial during the Leo M. Frank clemency hearings of 1915.

During the investigation the plant's janitor Jim Conley also became a suspect. It eventually was revealed that he wrote the notes but he claimed Leo Frank had paid him to do it. The police believed Conley to be the murderer and that he had planned to rob another employee but found Mary an easier target.

The police planned a confrontation between Frank and Conley but Frank backed out. As a result, it was interpreted as an admission of guilt.

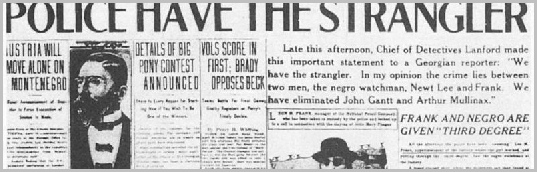

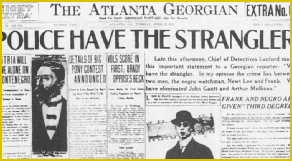

On 24 May 1913, Frank was indicted by the Grand Jury and the trial began on 28 July. On 25 August, Frank was found guilty of the murder.

There was jubilation in the streets when Frank was convicted and sentenced to death. By June 1915, his appeals had failed. Governor John M. Slaton, stating there may have been a miscarriage of justice, commuted the sentence to life imprisonment, to great local outrage. A crowd of 1,200 marched on his home in protest.

The Marietta Vigilance Committee had sent notices to the Jewish businesses and residences for all Jews to leave Marietta by Saturday night June 29, 1915. "We mean to rid Marietta of all Jews by the above date. You can heed this warning or stand the punishment the committee may see fit to deal with you".

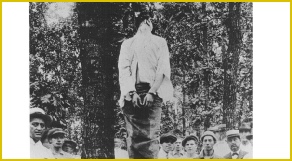

Two months later, Frank was kidnapped from prison by a group of 25 armed men who called themselves "Knights of Mary Phagan". Frank was driven 170 miles to Frey's Gin, near Phagan's home in Marietta, and lynched. A crowd gathered after the hanging; one man repeatedly stomped on Frank's face, while others took photographs, pieces of his nightshirt, and bits of the rope to sell as souvenirs.

The true murderer was not confirmed until 1982 when Alonzo Mann, Frank's office boy at the time of the murder confessed that he had seen Jim Conley at 12:05 in the factory alone carrying Mary's body to the basement ladder. Conley had threatened to kill him if he reported what he had seen.

To this day, pilgrims make their way to Mary's grave and often leave flowers, dolls and other childhood tokens.

The Lady in Black

A second famous grave in the City Cemetery is that of a marble angel marking the grave of Mary Annie Gartrell. After Mary Annie's death, her sister would walk twice a week from Atlanta to visit her grave. Lucy Gartrell, a musician and native of Cobb County erected the statue in her sisters memory and made the pilgrimage for over 45 years, always wore black mourning clothes. As a result of her devotion, she earned the nickname of the "Lady in Black."

William Gapers G. Harris’s tombstone

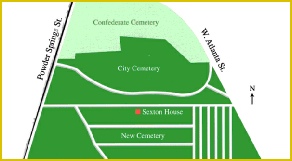

Map of the Old City Cemetery and the Confederate Cemetery.

Mary Phagan

Leo M. Frank

Front page news announcing the arrest of Frank.

The lynching of Leo M. Frank

The angel marking the grave of Mary Annie Gartrell.

| Paranormal Books |

| Apparitions |

| Cryptids |

| Demons |

| Orbs |

| Poltergiest |

| Residual Hauntings |

| Shadow People |

| West Demons |

| Ouija and Zozo |

| Exorcisms |

| Anneliese Michel |

| Ronald Hunkeler |

| Anna Ecklund |

| LaToya Ammons |

| George Lukins |

| Christian Demon texts |

| Roman Rite 1614 |

| Roman Rite 1998 |

| Eastern Demons |

| FAQ |