Last Gasps

Paranormal

The South’s science-based team!

Our trained investigators are here to believe you. Most importantly, we are here to solve the problem...no matter what it takes. Our services are always FREE.

© 2023 Last Gasps paranormal. Links | Terms and Conditions

The Exorcism of George Lukins

Disclaimer: This work has been completed as an educational tool for students of history, religious and paranormal studies. The author wishes to discourage any use of this work in conjunction with paranormal field investigations of demons.

Written by Kyle T. Cobb, Jr.

Nos tibi credere.

A Case History

The Exorcism of

George Lukins

In 1787, George Lukins was 44 and lived in the village of Yatton, just outside of Bristol. He was originally trained as a tailor, but earned his living as a "common carrier, a singer, actor of Christmas mummeries, [and] a ventriloquist." He was described by his neighbors as being of "extraordinary good character from his childhood, and had constantly attended the church and sacrament."

Beginning in 1769 , he had suffered from "fits of an alarming nature," which most likely was epilepsy. Lukins claimed that he had been fine until he was performing an old mummer's play at Christmas time when he had felt a "Divine slap" which felled him to the ground and left him possessed by demons. According to witness, Lukins was performing late one night at the house of a Mr. Love and after a number of strong beers became inebriated. In fact, he was so drunk, he was escorted home by two neighbors named Avery and Read.

After this night of drinking, Lukins began experiencing seizures where he could not speak. Stories about Lukins also asserted that he would make strange animal sounds, including barking like a dog. He would also argue with himself and act violently. The fits always began and ended with "a strong agitation of the right hand." Witnesses also reported that Lukins "cannot hear any virtuous or expression used without pain or horror." Lukins is also described as being an "emaciated and exhausted figure."

In spite of the violent attacks, Lukins continued working but gradually the need for medical treatment became apparent. According to Reverend Wake, whose late uncle had been vicar of nearby Backwell, in 1775, the parish gathered 15s and sent Lukins for examination at St. George's Hospital in London for almost 20 weeks. According to hospital records, Lukins was admitted to the hospital on 3 May 1775 and was discharged 8 October 1775.

While in the hospital, Lukins was allowed visitors and experienced no seizures. However, doctors at the hospital were unable to solve Lukins epilepsy and pronounced him incurable. As Lukins's conditioned worsened, Lukins was placed under the care of a surgeon from Wrington named Smith. Unfortunately, Smith was also unable to improve Lukins's condition. A doctor James of Wrington and a doctor Short of Bristol examined Lukins and found him to be "afflicted with a grievous hypochondriak disorder." A doctor named Whitchurch in Blackwell prescribed laudanum but even with extremely heavy doses, there was no relief.

One of the Doctors that examined Lukins was Samuel Norman. According to Norman, "To prove himself bewitched, he gave me and others many relations of the power of witches, their iniquitous practices and punishments for them."

It is alleged that during the same time Lukins was consulting doctors, he also sought the help of several "cunning-folk," or magic practitioners, to solve his problem. A woman from Bedminister prescribed rolled-up brown paper with pins driven in and then burnt in a fire during the fits. Other "cunning-folk" insisted that "indigent and infirm old people" had bewitched him. Lukins was so convinced of a magical cause that he even attacked an elderly woman in an attempt to draw her blood.

Following his hospital stay, Lukins lived at the home of his broth in Yatton for a short while. Unable to handle Lukins, eventually George was forced to move into the house of Richard Beacham. While staying with Beacham, the fits seemed to end. Even after moving out from the Beacham homes, Lukins was episode from for over a decade.

In 1787, the seizures returned. This time instead of claiming that that attacks had come from witchcraft, Lukins asserted the cause was possession by the Devil.

On 7 June 1787, Lukins was staying at a home on Redclift Street own by a man named Westcote. While there, Lukins experienced an event which was described by witnesses as having left them in a state of "horror and amazement at the sounds and expressions" that they heard.

Sarah Barber, a member of the Temple Church for nine years, knew of Lukins's condition because her husband was from the same village. She approached her Anglican vicar, Reverend Joseph Easterbrook on Saturday, 31 May 1788 and asked him for help. Barber claimed that:

"she had seen a poor man afflicted with a most extraordinary malady, who when in fits would sing and scream in various sounds, scarcely human, and which fits to her knowledge he had been troubled with for near eighteen years. He had tried several medical gentlemen, but in vain. The people of Yatton conceived him to be bewitched; that he himself declared he was possessed of seven devils, and that nothing could relieve him but the united prayers of seven clergymen who could ask deliverance for him in faith."

The claim of seven demons is significant because of the New Testament assertion that Mary Magdalene was possessed by seven demons.

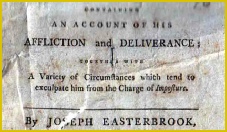

According to the Easterbrook's writings he was "little expecting that an attention to such a pitiable case would have produced such a torrent of opposition, illiberal abuse upon the parties concerned in his relief."

Reverend Easterbrook met with Lukins several times in the church to determine if he was indeed possessed. Once such a determination was made, under the 1604 canons of the Church of England episcopal authority was required to perform an exorcism.

Deciding Lukins was indeed in need of an exorcism, Easterbrook asked for a meeting to discuss the remedy to the possession. In addition to Easterbrook, three other priest attended:

- Reverend Richard Symes, Rector of St. Werburgh

- Reverend Robins, the Precentor of the Cathedral

- Reverend James Brown, Rector of Portishead

While it is unclear why the bishop, Christopher Wilson, did not participate in the meeting, ultimately, Easterbrook's petition to perform the exorcism was rejected. Even so, Easterbrook continued in his attempts to get Lukins cured and contacted the Anglican priest Reverend John Wesley, one of the founders of the Methodists movement. While Wesley declined to participate, six other priests agreed to perform the exorcism. A committee of Wesleyan ministers was assembled to make preparations.

One of the priest, Reverend John Valton previously knew Lukins and wrote of him:

I personally knew him; a youth about 18, short in stature, and meagre in aspect. He had frequent fits or paroxysms, and was sometimes affected like the Pythonesses, or rather like the furies, mentioned often by Herodotus and ancient writers. He was cruelly distorted, and uttered foul language; but was often heard to say that he should be delivered, if 7 ministers should pray with him.

Prior to exorcism Reverend John Valton met with Lukins and stated:

Some time ago I had a letter requesting me to make one of the seven ministers to pray over George Lukins. I cried out before God, "Lord, I am not fit for such a work; I have not faith to encounter a demoniac." It was powerfully applied, "God in this thy might." The day before we were to meet, I went to see Lukins, and found such faith, that I could then encounter the seven devils which he said tormented him. I did not doubt but deliverance would come. Suffice to say, when we met, the Lord heard prayer, and delivered the poor man.

At 11 AM on Friday, 13 June 1787, Easterbrook assembled seven witnesses and six Wesleyan Ministers to perform the exorcism in the vestry room of the Temple church. The participants at the exorcism were:

Priests Assistants

- Reverend Joseph Easterbrook

- Reverend John Broadbent

- Reverend John Valton

- Reverend Jeremiah Brettle

- Reverend Benjamin Rhodes

- Reverend Thomas Mac Geary

- Reverend William Hunt o J. Westcote

- J. Lard

- T. Delve

- Rees

- Deverel

- Tucker

- Gwyer

- Nathaniel Gifford

The Methodist exorcism ceremony resembles the Catholic rite in many ways. The ritual consists of adjurations and commands for the demon to depart. These commands are accompanied by prayers and hymns. Ironically for this case, all of these rituals were expressly rejected by the Church of England as well as the other Protestant denominations.

When the priest begin singing hymns, Lukins's face distorted, his body began to spasm and he was subject to "strange agitations." At times, Lukins would speak in a "deep, hoarse, hollow tone" claiming to be under the influence of an invisible agent. Lukins would shout blasphemes in other voices (male and female). He would sing and laugh in these voices and periodically declare himself to be the Devil. Lukins then "vowed eternal vengeance on the miserable objects, and on those present for daring to oppose him and commanded his 'faithful and obedient servants' to appear, and take their stations." Lukins became violent and it was difficult for two strong men to hold them.

As the priest prayed, Lukins sang a Te Deum to the devil in different voices saying, "We praise thee, O Devil, we acknowledge thee to be the supreme governor…"

Reverend Mac Geary adjured the Devils in Greek and in Latin but according to the priest, the "pretended Devils were so unclassical as not to be able to reply."

One priest demanded that Lukins speak the name of Jesus. Lukins would reply "I am the Devil" instead. A faint voice also seemed to say "Why don't you abjure?" The priests commanded in the name of the trinity that the evil depart. Lukins would also swear "by his infernal den," that he would not leave. The use of this particular phase echoes words from the February, 1678 publication by John Bunyan discussing a Christian's journey toward understanding.

The demon responded, "Must I give up my power?" Then Lukins began howling. As the priest continued their prayers, Lukins shouted, "Our master has deceived us! … Where shall we go?"

"To hell, and return no more to torment this man," the priest replied.

After two hours of repeated prayers, Lukins announced in his own voice, "Blessed Jesus." Then he praised God for deliverance and said the Lord's Prayer. After that point, Lukins seemed to experience no other issues.

If they thought this would be "away from prying eyes" they were wrong - the astonishing noises emanating from the vestry quickly produced a crowd of nosey-Parkers, and within days, news of the goings-on in the vestry was carried around the whole country.

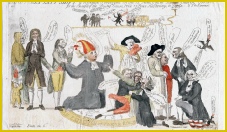

At the time of the exorcism, many writers asserted that Lukins was an impostor. One critic of the exorcism as a local surgeon named Samuel Norman who wrote and printed a pamphlet called "Authentic anecdotes of George Lukins, the Yatton demoniac". For his part, Norman led a vocal opposition showering ridicule on the clergy that had been duped by Lukins. Norman also asserted that another motivation for Lukins deception could be an excuse for the return of the Roman Catholics.

Other members of the medical community also became involved in the debate but, in general, the response was that it "argues very ridiculous credulity on the part of the reverend gentlemen concerned." A Doctor Box of Wrington that had been one of Lukins's many doctors declared him to be nothing more than a cheat.

Witnesses to Lukins's events asserted in publications that his first seizure was simply a fit of drunkenness. Lukins always predicted his fits prior to their occurrence. While the fits would always begin with a clenched hand, "in every one of which, except in singing, he performed not more than most active young people can easily do." After money was collected for him, "he got very suddenly well."

Other religious writers such as Reverend John Wesley, asserted that the Lukins case was a miracle and proof of Divine providence. In defense of the exorcism, Easterbrook wrote that the possession was authentic and to deny its reality would be to claim that the power of the Lord had diminished since Biblical times.

At least three publications were printed and circulated following the exorcism debating the Lukins authenticity. As mentioned earlier, Samuel Norman let the call that the possession was faked in his two publications, Authentic anecdotes of George Lukins, the Yatton demoniac (1788) and The great Apostle Unmasked (1788). For his part. Reverend Easterbrook wrote An appeal to the public respecting George Lukins and had two printings created. Both Norman and Easterbrook have been used in producing this history.

As to whatever became of George Lukins, the history is slightly confused. In 1882, Nicholls and Taylor asserted in their work that Lurkins lived a pious life and no longer experienced seizures. He is also said to have become a respected member of Wesleyan society in 1798. Reverend Valton in his writings claimed that following the exorcism Lukins was employed as a bill sticker by R. Edwards.

However, there is indications in the Yatton parish records in 1788 that they provided George Lukins "temporary relief" of 10s 6d. He was also promised 9s in the future ""provided he goes to Mr. Say and attends him in any kind of work he can do, but George Lukins has refused to do it, saying he shall go to Bristol and not come back till he is forced and that shall not be till Bedminster parish brings him home with an order."

A Lovell satire, entitled Bristol, mentions Lukins:

Lo, Lukins comes, and with him comes a train

Of Parsons famous for lack of brain;

With owl-like faces, and with raven coats,

Their solemn step their solemn task denotes,

By exorcism, prayers and rebukings,

To drive seven sturdy devils out of Lukins.

Following the exorcism of Lukins, there are records of a number of other lower profile exorcisms held by the Methodists around Bristol as well as a few by the Catholic minority.

St. George's Hospital as seen in 1836

Ruins of Temple Church in Bristol

Easterbrook’s Pamplet on the exorcism

The Imposture Last Shift. Note the caption at the bottom says an Exhibition of Fools and Rogues

| Paranormal Books |

| Apparitions |

| Cryptids |

| Demons |

| Orbs |

| Poltergiest |

| Residual Hauntings |

| Shadow People |

| West Demons |

| Ouija and Zozo |

| Exorcisms |

| Anneliese Michel |

| Ronald Hunkeler |

| Anna Ecklund |

| LaToya Ammons |

| George Lukins |

| Christian Demon texts |

| Roman Rite 1614 |

| Roman Rite 1998 |

| Eastern Demons |

| FAQ |